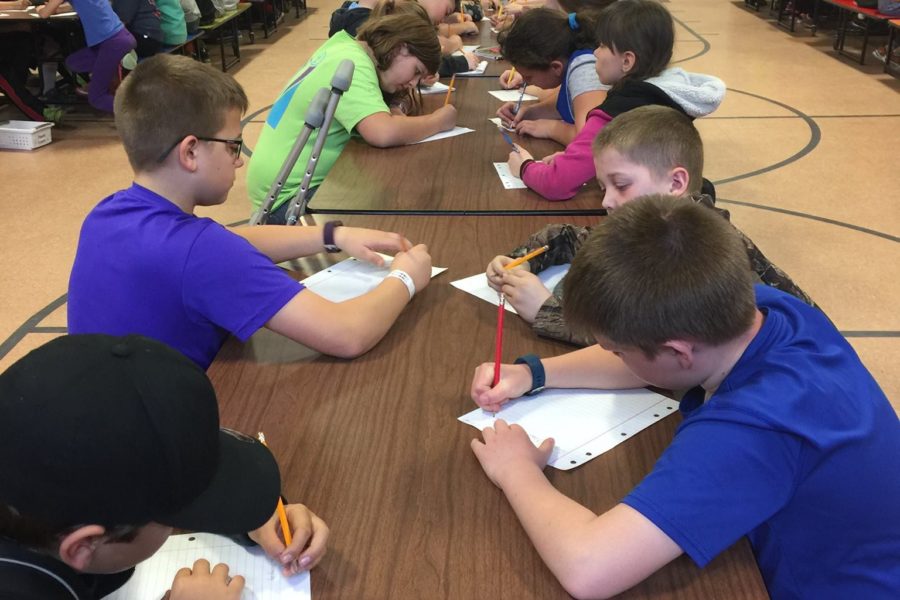

The process of writing begins before you actually put pen to paper (or words on a screen). Many people find “pre-writing” helpful, notes or an outline to help guide their writing. Some prefer to just jump in and start writing and see what happens. There’s no “right” way to go about writing. Some kids are intimated by writing in class, the daunting prospect of having to just sit down and write. How can we help support these students in beginning the drafting process, sometimes the most frustrating or intimidating step?

I tell my students to just get it all out on the page in early drafts and worry about tying it all together and finessing the work later. Often, the blank page can be daunting and, if you give yourself permission to write rough work first, everything else will follow. Don’t worry about it being “good,” yet, I always say. Just start. As David Wagoner wrote in his poem, “The Source,” “Only begin, and the rest will follow.”

Remind students their first draft is not a final draft or a polished piece of work, and no one expects it to be. At CLiF programs, our presenters talk about their process for creating books and stories, and they often emphasize how many drafts they go through before reaching a final product.

Reading specialist (and former CLiF Board of Advisors member) Bruce Johnson says, “Some children often want to write down their work and get it perfect the first time. It needs to be clear that writing needn’t be perfect the first time. Nor should it be perfect the first time. Explain that writing is a process, and that it’s appropriate, and even preferable, to just write something down, see where it goes, and to explore. Then go back and revise and improve.”

Writers rework their ideas, revise, and complete many drafts before publishing a piece. This is important to emphasize to students, that everybody starts somewhere and puts a lot of work into the final product, that it won’t be perfect (or even close!) the first time around, or maybe the second or third.

A few years ago, I taught fiction at a Governor’s Institute Winter Weekend (for high school students) at Goddard College. On the first day, my co-teacher and I gave an ice-breaking assignment and the students got to work right away. One student appeared nervous, looking around at the other students writing away, and sheepishly came up to me. “I can’t just write,” he confessed. “I need to go for a walk first.” I told him that this was fine, and as long as he stayed in the building, go for it. By the end of writing time, he hadn’t written a word and seemed embarrassed. I told him it was fine if he didn’t get a draft down in the allotted time, and would he like to just share what he’d come up with? What came out was an amazing story that he had yet to write down but had formulated completely in his mind. He worked on it throughout the weekend, asking me to read the next draft and the next. He was excited about the ideas he’d come up with and the fear and shame of not being inspired right away seemed to fade. Now, I recognize that school settings don’t necessarily accommodate these kinds of needs, but many students struggle to just sit down and write (so do many professional writers). One thing that could be helpful is suggesting they jot down a list or an outline of their ideas before they start writing to get the creative juices flowing.

I got the chance to teach at the Governor’s Institute’s summer Young Writers program at Bennington College last summer. I taught a genre-blending workshop and encouraged students studying various genres to play with their form, write a poem if you’re a story writer, write a story if you’re a poet. We looked at Maggie Nelson’s Bluets (one of my favorite books) and I had them pick their own color and write a list of words it made them think of. Then they turned their list into a poem. Then they took a line from their poem and crafted it into a story. At the end of class, when we debriefed, one student said, “I’ve never written a poem before and I wouldn’t know what to do if you just told me to write a poem, but by making the list, I organized my thoughts and wrote a poem.” Exactly what I was going for, encouraging students to get out of their comfort zones, experiment, and take away some of the intimidation of writing. Pre-writing exercises can help students organize their ideas, prepare to put them on paper, and alleviate some of the frustration of beginning from scratch.

I know you want your students to have a firm command of spelling, grammar, syntax, and structure, but this doesn’t all necessarily come at once, and if they continue to be bogged down by errors and corrections, some students may conclude that they’re not good enough, they can’t write, they keep getting it “wrong.” So encourage them not to focus too much on spelling or grammar in the first draft. Tell your story first, then go back and revise. This is what I keep telling the student I work with at Central Vermont Adult Basic Education. She’s writing a novel as part of her high school diploma graduation plan. We meet to discuss it every week and, every week, she arrives excited to talk about what she’s been working on and our conversations often lead to new ideas. Now, her spelling, grammar, and structure need a lot of work and we do sometimes talk about this. Every week, I ask her what she wants to work on, what’s exciting her, and if she has ideas for the next chapter and wants to keep moving forward, great. Write what’s pulling you, I always say. Write the thing inside you that’s itching to get out, the idea that won’t leave you alone. We’ll go back and worry about grammar and spelling later. After a few months of this, she came to me and said she was ready to revise. Fantastic. So we looked at the errors in her early chapters, what sections could be improved, and how her ideas had changed since writing Chapter One. Again, I recognize that traditional school settings don’t necessarily allow for this, but I think it’s important not to stifle a student’s creativity or leave them feeling bad because they can’t write perfectly at the drop of a hat.

Free writes can help intimated students get started, and offering some prompts or opening lines can help conquer that pesky blank page.

That student who needed to go for a walk before writing? We really connected in that moment; I had given him permission to write in a way that worked for him, and reminded him that it was OK to use his own process. The next year, he asked me to be his Senior Project mentor and we Skyped and talked on the phone throughout the year as he worked on an original play. I was getting my MFA in fiction from the Bennington Writing Seminars at the time, and I recall one day being particularly frustrated by a draft I was working on. I just couldn’t figure out the ending and had been staring at the same page, writing and deleting, for hours. The phone rang and I literally said “Thank God,” out loud, eager for the distraction. It was my student. He was having a hard time working on his next scene, he said. He couldn’t seem to figure out what to write next. I was honest with him and told him that I’d been struggling to write that day, too. We talked through it, discussed our ideas, and when we got off the phone, we both got to writing.

Having small group discussions about what you’re working on can be a good reminder that all writers get stuck and ideas don’t always flow freely. Talking through ideas and sticking points can be helpful. Offering some guided questions for discussion can help move ideas forward. What do you want readers to get out of your piece? What’s your goal for the piece? What feelings or ideas are you trying to convey?

Starting with a prompt, topic, or leading sentence can help students generate ideas. You might suggest they start each sentence with the same phrase. Some examples teachers I’ve worked with have offered include “start every sentence with “Because'” (thanks, CLiF presenter/poet Geof Hewitt) or “I remember” (thanks to Ken Harvey, courtesy of Joe Brainard’s book, I Remember), then write for as long as you can. Making the goal just to write for a period of time without worrying about the end product can also help generate new ideas and break down intimidation or frustration.

Johnson writes, “Regardless of whatever problems come along, remember to praise the efforts. Some children will become successful writers without much intervention. Other children may see writing as a struggle. It needn’t be a struggle. Just keep working on writing like a jigsaw puzzle, and put it together piece by piece. Try to praise as much as possible.”

Here are a few of his suggestions for prompt ideas:

Possible Story Starters

- Write about your day, starting from the minute you stepped out of bed, and continuing to this writing session.

- Look out the window. Write down all that you see.

- Create a list of words to describe a person you know.

- Draw a picture of something you like to do. Then write about it.

- Write 5 possible characters and 5 possible activities for those characters. Then write a fictional story using 1 of those 5 characters.

- Create a conversation with a goblin who flies on a magic carpet.

- Write about the clown who was laughing on top of a mountain. Be sure to include “why”.

- Read a newspaper article at random and respond with your thoughts on the topic.

- Top 10 tips for children or teens entering your school.

- What are your goals for the coming year?

- What is the best way to spend a rainy or snowy day? Describe 10 activities to do.

- My favorite thing to do is….

Scholastic Story Starters also has some great prompts for kids.

Happy writing!

Erika Nichols-Frazer is a writer, editor, and Communications Manager at CLiF. She has an MFA in Fiction from the Bennington Writing Seminars and is a reader for the journal Literary Orphans. She is a volunteer Writing teacher at Central Vermont Adult Basic Education. You can find her work and blog at nicholsfrazer.com.

Another great article! Thanks Erika.