CLiF Presenter author/illustrator Jason Chin shares during his presentations his process for creating and revising his picture books (you can watch this video on Jason’s presentation at JFK Elementary in Winooski, VT this summer). He shows kids the various drafts his work has gone through to become his non-fiction picture books. He tells them about how he wants his work to be the very best it can be before audiences see it. It’s an important lesson for kids to see that their favorite authors don’t just come up with the perfect idea the first time, that successful writers go through many drafts before their work hits shelves.

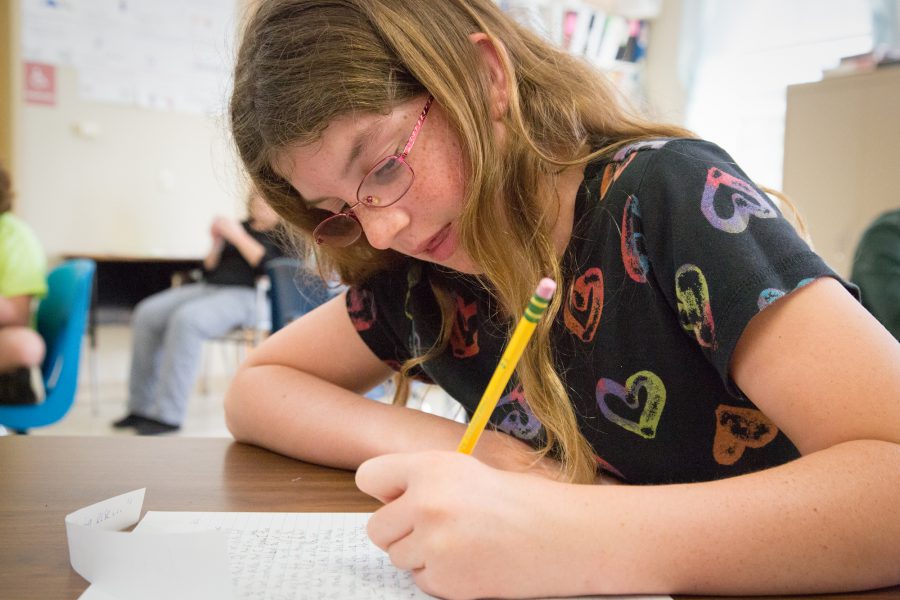

One of the biggest hurdles for new writers is understanding that your first draft (and your second, third, fourth, and so on) is just the beginning. The real work is in revising. Your writing often takes a dramatic journey from its first draft to the final piece. Sometimes, the finished product barely resembles that first draft. Some find that initial blank page the most intimidating part, but for many, revising can be the most challenging aspect of the writing process. There’s a reason that first draft is often called a “rough draft,” because it’s just that – rough. It’s a beginning from which the ultimate work will sprout, but it’s got a long way to go, no matter how good the writer is. It’s important to remind young writers that suggestions for improvement don’t mean the work isn’t good; it can always be better.

Some of the students I’ve worked with want me to tell them exactly how to “fix” something, and though I can help offer some ideas or identify areas that I’m really interested in or where I have questions, I always emphasize that they are in control of their work and the final changes are up to them. Aside from grammar and spelling mistakes, there is no “right” way to tell a story and it’s a good idea to avoid telling students they should or have to write something in a certain way. Offer advice, such as, “You might want to consider…” or “As a reader, I’m really interested in this part and would like to know more about that,” or “I was a little confused here. Here are some suggestions for ways you might make this a little clearer.” It’s important to frame advice that gives the writer the power to determine how to best achieve his or her goals. Emphasize what’s working well and then suggest areas they might be able to improve.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the art of revising as I revise my short stories into a 100+-page thesis for the Bennington Writing Seminars. I’ll be graduating from the BWS’ Master of Fine Arts program with a degree in fiction this coming January, so these next few months are busy with revisions, taking the stories I’ve written over the past two years and compiling them into a collection that will (eventually) become a book. Over the past two years, my professors have asked for a mix of new work and revisions. We’re encouraged to always be making the work better, taking into account the feedback from our professors and peers and honing the piece into the best version of itself we can create. Now that I have most of the work I’ll submit for my thesis, the work has shifted into revision mode.

Typically, when I sit down to revise a piece, I’ll make a list of what questions other writers asked, what they liked and what areas they thought had potential for improvement. Sometimes the feedback will be contradictory: one member of the workshop loved this part, another thought it should be cut; someone said there’s too much exposition or dialogue, someone else wanted more. It can be daunting and sometimes confusing to put into action. I usually read through the piece first, then read all the comments and take notes, then read through it again with an eye for how to put the notes I agree with into action. Sometimes the feedback I receive isn’t the direction I’m interested in going with the story, but it can still be helpful to know what’s pulling readers, what they expect and want out of the story, even if it differs from my goals. Often, I’m surprised by what my readers picked up or connected with, which is immensely helpful as I revise. I also often create a list or mind map of different directions the story could take, choices the character might make, reactions that other characters might have. I won’t write all of them, and maybe won’t even write any of them, but it can help me think of possible directions when I revise.

Engaging peers in the conversation about writing can be productive for the writer and those giving feedback, but the workshop facilitator (such as a teacher) needs to set ground rules for positive, constructive conversations that are helpful to the writer. Model positive workshop behavior, such as starting with what’s working well, giving specific advice, rather than a place to list everything ‘wrong’ with the piece, and use the workshop for a broader conversation around what the writer is doing and how. Many kids have never been in a workshop setting and creating a space for them to have constructive conversations about each other’s work can be inspiring and helpful. It’s also useful to not just focus on always creating something new, but to keep revising a piece until it’s the best version it can be.

Every writer has his or her own approach to revision, and his or her own ideas about when it’s most helpful in the process to get feedback. Some writers like to have a really polished product before they share it with anyone. I tend to prefer to hear what’s working and what needs improvement earlier on in the process, when I’m still figuring out what readers will take away from the piece. I often share an earlier draft with my trusted writing group, who I know will guide me in the right direction, then get feedback again as my drafts take twists and turns. Sometimes I’ve tried to implement comments I’ve received, but that don’t really seem to be working the way I want them to. This can be a good time to get more feedback. If I’m not sure about a change, I’ll save multiple drafts so I can go back and see what’s working, occasionally marrying different drafts together.

Here are a few questions I ask myself when revising:

-What do I want the reader to take away from this story, poem, or essay?

-How do I want the reader to feel when they read this?

-Are my goals coming through in this version? Are readers connecting with the parts I want them to? (This is where feedback comes into play and can help you identify the disparity between what you intend for the piece and how it’s being received in this version.)

-Are there areas where readers are getting confused or bumped out of the story?

-Are there sections that are weighing the story down and could be cut?

-Am I entering the story at the most effective place (I once worked with a writer who liked to say “The beginning is never actually the beginning; it’s where you choose to enter the story.”)?

-What characters are readers identifying with? Why?

-What did my readers pick up on that I missed?

I always enjoy getting to see pieces for the second or third (or fourth, fifth, or sixth) time in my writing group or in workshop. It’s delightful to see the transformation of someone’s work throughout their revising process. In several cases, I’ve had the pleasure of seeing a friend’s book in print that I saw an early draft of and watched it take shape into the book that’s now on my shelf.

What have you found helpful when revising?